How Misunderstood Minds Were Failed by the System

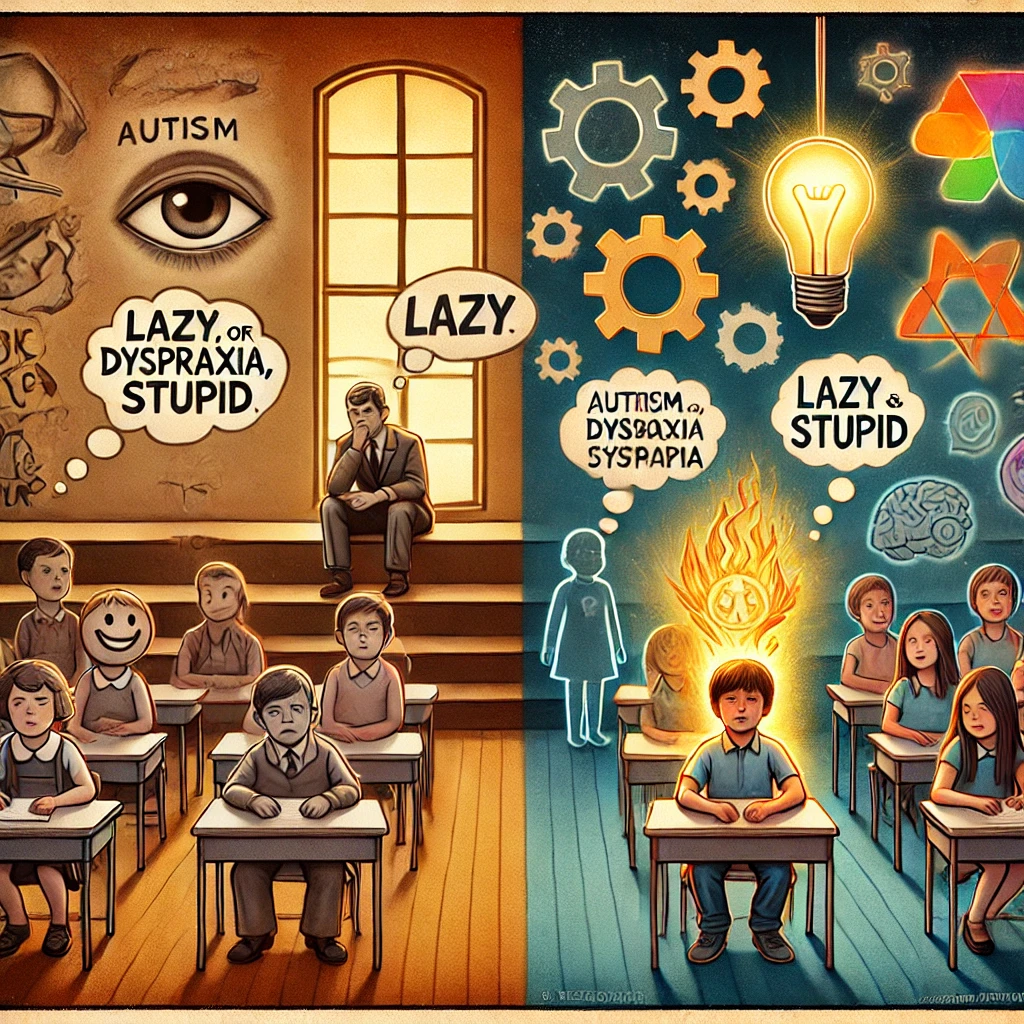

In the 1960s and 70s, if a child couldn’t keep up in school, they were labeled “thick,” “lazy,” or “stupid.” There was little room for nuance, no recognition of learning differences, and certainly no talk of neurodivergence. The idea of a “spectrum” didn’t exist in mainstream discourse. A student who couldn’t write neatly, struggled to coordinate their body, or had difficulty processing language or social cues was often simply cast aside. They weren’t offered support — they were told to try harder, behave, or accept their supposed inadequacy.

Fast forward to today, and we understand so much more. Conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD), dyspraxia (also known as developmental coordination disorder), and dysgraphia (a learning disability affecting writing) are widely acknowledged. Neurodiversity — the idea that different neurological makeups are not deficits but variations — has entered the public consciousness. But while awareness has grown, a lingering myth persists: that those who learn differently are somehow less intelligent. And this myth has deep roots.

It’s important to understand how the school systems of the mid-20th century reinforced rigid norms of intelligence. Standardized tests, rote memorization, and a narrow focus on reading, writing, and arithmetic meant only certain types of learners were praised. If a child couldn’t express themselves on paper or found handwriting painful due to dysgraphia, their ideas were often ignored. If a student had trouble with motor skills due to dyspraxia, they were labeled clumsy or careless. If a child on the autism spectrum found social interaction difficult or responded to sensory overload with meltdowns, they were misunderstood or even punished.

Many of these children grew up internalizing the message that they were stupid. Decades later, these same people — now adults or elders — may still carry that weight. And here’s where compassion becomes crucial. Some older individuals who seem dismissive of “labels” like autism or dyspraxia may not be being willfully ignorant. Rather, they may be defending themselves from painful memories of being unfairly judged and humiliated. To them, the idea of a diagnosis might feel like a luxury they were never afforded — or worse, a reminder of how they were failed.

This isn’t to excuse ignorance or denial, but to offer a deeper lens. Patience and education can open the door to understanding. Many older adults who initially scoff at neurodivergence will, when gently guided, recognize those same traits in themselves or their classmates from long ago. Some may even feel relief at finally having a name for what they endured in silence.

The myth of stupidity thrives in a world that values conformity over diversity. But intelligence is not a single track — it is a mosaic. People with autism may have extraordinary pattern recognition or deep-focus abilities. Those with dyspraxia often develop creative problem-solving skills to navigate a world not built for them. Individuals with dysgraphia might be gifted storytellers, even if their handwriting struggles to capture it.

Breaking the myth means changing the way we talk about intelligence, success, and ability. It means valuing different ways of thinking and recognizing the systemic failures of the past. The label of “stupid” was never about the child — it was about a society that didn’t understand.

We owe it to those who grew up misunderstood to rewrite the story — not just for the young people who benefit from today’s better awareness, but for the many older people who still carry the shame of labels they never deserved. A little empathy, a willingness to listen, and the courage to question long-held assumptions can reveal the truth: they were never “thick.” They were always more than what they were told.